Task Design in Online One-to-One Classes with Young Learners

Originally published in Language Teaching for Young Learners.

1. Introduction

In November 2017 I accepted a job in an online school. I took on responsibility for developing materials aimed at improving students’ spoken English. I was also in charge of overseeing the quality of one-to-one lessons for 10,000 teachers and 100,000 students. Several things struck me about my new context. Offline coursebook materials were used in these online one-to-one classes, even though they had been created for a different context. The quality varied greatly between lessons depending on the teacher. The school also provided minimal support to teachers. Teachers completed around three hours of self-study training before teaching their first class. After induction, teachers were rarely observed unless they received complaints.

This new context also presented many opportunities, such as those for observing lessons. Unlike in offline contexts, it was possible to observe materials in use by viewing recordings of lessons. These video observations neither disturbed learners and teachers, nor influenced their behaviour. These factors sparked my interest in using observations to investigate how effective the materials in my context were at helping learners improve their spoken English. I started this research project in 2019. At that time, my concerns about materials in online young learner language classes were something of a fringe interest. One year on, that changed. The Coronavirus pandemic pushed learners and teachers across the globe into online classes, making the evaluation of online teaching materials more relevant than ever before.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Online Materials Design

Materials play an important role in determining what happens in classrooms. Cunningsworth notes that “probably nothing influences the content and nature of teaching more than books and other teaching materials” (1998, p. v). If this is true offline, it must be even more true online. In my school, the materials, or “courseware”, take the form of a PDF or PowerPoint file. These are displayed at all times in class, occupy the majority of the space on the screen, and cannot be minimized. Literally centre screen and proverbially centre stage, the courseware continually prompts interactions between teachers and learners.

There is rising interest in online interactions and a growing body of literature on online communication (Ellis, et al., 2019). However, relatively little has been written about how online materials should be developed. Tomlinson and Masuhara sum this up saying, “Although there have been radical developments in the use of new technologies to deliver language learning materials… there are very few books (or even articles) that focus on the pedagogical principles of these materials” (Tomlinson & Masuhara, 2018, p. 6). One principle for online materials design is to encourage meaningful communication. Meaningful communication is important in all contexts, including online. In fact, research suggests that synchronous online interactions may be even more beneficial in promoting L2 learning outcomes than face-to-face interactions (Ziegler, 2016).

“Facilitating communicative competence… is particularly crucial for [online] language tutors” (Hampel, 2009, p. 40). Communicative competence can be achieved through appropriate tasks. “Well designed tasks are needed to impact student outcomes… by promoting successful and satisfying online exchanges” (Blake, 2017, p. 124). Effective online interactions require tasks which focus on meaning (Hampel, 2006) and should be tailored to the online environment. The use of offline tasks in online lessons is inadvisable (ibid). Instead, materials writers ought to “ensure that tasks are appropriate to the medium used and… take into account the affordances (i.e. the constraints and possibilities for making meaning) of the modes available” (Hampel, 2006, p. 111).

2.2 Meaningful Communication

Meaningful communication is important in online materials design, but what role does it play in promoting second language acquisition (SLA)? Swain (1995) claims that meaningful communication gives learners opportunities to produce comprehensible output. This forces learners to express themselves in new ways, “at the cutting edge of their linguistic ability” (Ellis & Shintani, 2014, p. 208). This results in acquisition for both adults and young learners (ibid). Long (1983) views the role of meaningful communication differently. He argues that when meaningful communication breaks down, interlocutors must alter their speech to be understood. “When learners run into communicative trouble, they are likely to switch their attention from meaning to form long enough to solve the problem” (Long, 2015, p. 53). This negotiation of meaning “makes input comprehensible and… in this way promotes SLA” (Ellis, 1999, p. 142). This is true of both adults and young learners. However, young learners tend to use different strategies to negotiate meaning compared to adults (Oliver, 1998).

Despite its importance in SLA, meaningful communication is often absent from classroom interactions. Nunan notes that “in communicative classes, interactions may, in fact, not be very communicative” (Nunan, 1987, p. 144). These interactions often follow the initiate-respond-follow-up (IRF) sequence (Ellis & Shintani, 2014). In this paradigm, teachers control the structure of classroom communication. Learners are passive, respond to questions from teachers, (Johnson, 1995) and have little control over classroom discourse. This is especially common in young learner classrooms. Often children “learn songs and rhymes, some basic vocabulary and carefully rehearsed dialogues, but they rarely progress further, and typically they are unable to express their own meanings spontaneously” (Pinter, 2011, p. 91). Not only are students often unable to express their own meanings, but some teachers also discourage them from doing so. In many classrooms, “when students attempt to use their own words, the teacher corrects them” (Ghosn, 2003, p. 296).

Descriptions of meaningful communication tend to focus on either how communication occurs or the conditions necessary for communication to be considered ‘real’. Suggestions for these conditions fall into one of three categories:

1. When students say something “real”. For example, “comprehending and expressing real thoughts” (DeKeyser, 2007, p. 292) or when the learner is thinking about meaning instead of form (Ellis, 2013).

2. When learners and teachers genuinely need to communicate information to one another (Ghosn, 2003). This could be “the process involved in comprehending and producing messages for the purpose of communication” (Ellis, 2013, p. 342).

3. When negotiation of meaning occurs. For example, “when learners experience a problem in comprehending something or when they are unable to clearly say what they want to say” (Ellis & Shintani, 2014, p. 144). This includes requests for clarification, confirmation checks and repetition (Nunan, 1987). Long has suggested that “the ‘best’ input for language acquisition is that which arises when learners have the opportunity to negotiate meaning in exchanges where an initial communication problem has occurred” (Ellis, 2013, p. 23). Through this process “learners make the link between meaning and form” (Ellis & Shintani, 2014, p. 145).

It is also important to consider how meaning may be communicated by learners. Learners may use ‘pushed output’. Pushed output occurs when learners attempt to convey meaning which lies slightly beyond their linguistic ability. This “stretch[es] their interlanguage to meet communicative goals” (Swain, 1995, p. 127). Not all communicative tasks push learners’ output. For example, productive tasks in the final stage of PPP (Present-Practice-Produce) lessons encourage learners to communicate using target language studied earlier in the lesson. How communicative this stage is will depend on how focused students are on communicating as opposed to using target language from earlier in the lesson. As well as using target language, learners may rely on language they have acquired previously. This could include single words, syntactically inaccurate language or even non-verbal communication.

Meaningful communication is especially important for young learners. Young learners tend to benefit less from form-focused instruction than older learners. “The search, for all learners of a language, is for ways of promoting meaningful communication but for children, this is not just a desirable facilitating and motivating factor but at the heart of what children need in order to learn” (Arnold & Rixon, 2008, p. 54). In spite of this, task-based learning with young learners is an under-researched area (Shintani, 2014). This is especially true online. One example which demonstrates this is Ziegler’s (2016) meta-analysis of the effectiveness of synchronous online interactions. None of the studies examined included learners under the age of twelve.

2.3 Communicative Task Design

One means by which materials may encourage meaningful communication is through tasks. Tasks have many benefits for language learning, such as:

· providing a rich input of target language.

· intrinsically motivating students. This is especially important for younger learners.

· focusing on meaning whilst also catering for learning forms (Ellis, 2009).

· generating “communicative output which can become valuable auto-input” (Tomlinson, 2020, p. 33). This allows learners to “benefit from the ‘input’ that their own output provides them with” (Ellis, et al., 2019, p. 32).

The following aspects of task design are particularly relevant to online materials:

· Predicted task outcome. This is the product of completing a task, such as a completed form or a list of differences between two pictures.

· Open vs closed tasks. The more open a task, the more potential ‘correct’ solutions there are available. Research with adults indicates that closed tasks lead “to more negotiation of meaning than open tasks” (Ellis, et al., 2019, p. 40).

· Information-gap vs opinion-gap. Information-gap tasks involve information exchange. Opinion-gaps require interlocutors to agree or disagree with each other. In one study, Ellis found that “negotiation of meaning was more likely to occur with tasks that required information exchange (i.e. information-gap tasks) than with tasks where information exchange was optional (i.e. opinion-gap tasks)” (Ellis, et al., 2019, p. 40).

· Topic. Different tasks focus on different topics. Preferences for topics will vary among learners (Ellis, 2013) and among teachers. The more familiar learners are with a topic the more they are likely to participate and be successful using a task. “A familiar task, topic, or discourse genre reduces cognitive complexity” (Long, 2015, p. 237).

· Task familiarity. The more learners practice a task, the better they get at performing it. Task familiarity tends to result in “increased fluency, use of more lexically complex language, and in some cases, greater accuracy” (Long, 2015, p. 244).

· Engagement. Affective and cognitive engagement are important in materials design (Tomlinson & Masuhara, 2018). These factors exert a strong influence on participation.

· Focused vs unfocused tasks. This is the extent to which a task encourages learners to use a particular linguistic feature. Focused tasks “elicit the use of the structure that has been targeted” (Ellis, 2019, p. 11). The less focused the task, the freer the learners are to use whatever language they wish. The more linguistic freedom learners are granted, the more meaningful the communication ought to be.

· Authenticity. “An authentic task is one that involves the learners in communication in order to achieve a context-based outcome rather than just to practice language or produce output” (Tomlinson & Masuhara, 2018, p. 6). This is similar to the concept of real-world tasks. Real world tasks are “based on a situation that can be found in everyday life” (Ellis, 2019, p. 28). However, young learners in EFL contexts tend to have few identifiable needs for English in everyday life. This makes authenticity difficult to define for this age-group (ibid).

3. Research questions

Thus far we have established that:

· Online task design for young learners is a largely unresearched area.

· Meaningful communication can promote SLA with young learners.

· Tasks in online materials have a large influence on the interactions which occur in the classroom. This includes how much meaningful communication occurs.

This study attempted to answer the following research questions:

· How effective are four tasks in supporting meaningful spoken language production?

· Which tasks are most effective in encouraging learners to engage in meaningful communication?

After answering these questions, I will put forward recommendations for online task design which supports spoken language production of beginner level young learners.

4. Methods

4.1 Context

All lessons in my school are one-to-one and delivered synchronously. These lessons last thirty minutes and use videoconferencing technology (similar to Zoom). Teachers and learners can see each other and also see the courseware. The courseware occupies the majority of the space on screen and appears identical for teachers and learners. This makes information-gap tasks (where one person can view information hidden from another) challenging. The materials used in this school are mainly scans of a coursebook. This coursebook was published in 2006 for face-to-face group classes in Hong Kong. Teachers are required to use one courseware in each lesson. Teachers cannot move to the next or previous set of materials during class.

4.2 Participants

The participants were seventeen teachers and learners at my online school. These teacher-student dyads took one-to-one classes together, usually twice per week. They were observed in these regular classes. I selected the participants by scanning recordings of one-to-one lessons which included the tasks to be evaluated. Teacher-learner dyads who used these tasks were chosen. Where possible, the dyads were kept consistent.

The teachers were mainly female (fourteen of seventeen). Eight were American, eight British, and one South African. They had an average age of 36. Only two had a recognized TEFL qualification. Six had no prior teaching experience to working at this online school. Eleven of the learners were female and six were male. The learners were around primary school age and beginner level. Unfortunately, no specific information on learners’ ages or levels was available.

Ideally, learners and teachers would be asked to ‘opt-in’ to this research. However, this was not possible due to school policies (even retrospectively). The anonymity of the participants has instead been ensured by removing names and other identifying information from the data presented.

4.3 Tasks

Four tasks were evaluated. Ten examples of each task were observed. The tasks were:

· Birthday party invitation. This task was taken from an offline coursebook. Learners partially dictated an invitation to their birthday party. While the learner dictated, the teacher typed the invitation. This task included some open elements. Learners could choose who to send the invitation to as well as the time of the birthday party. Other elements were more closed, such as the date of the party (presumably the learner’s birthday). The remainder of the task was more focused. Learners gave directions to the party location. This section included a choice of two pictures. These were designed to elicit previously taught target language. This task was on the last ‘page’ of a lesson at the end of a unit related to directions.

· Directions roleplay. This task was similar to an information-gap task. However, both the teacher and learner could see the same information (a shopping list and a map of the shopping centre). This task had a clear context and roles. Teachers, in the shopper role, asked for directions to shops based on items on the shopping list. Students, in the help desk role, provided directions, referring to the map. This task included a degree of openness. Some items on the shopping list could be purchased at more than one location. The task was focused, including sentence stems such as “Is there…?”, “Yes, there is/are. You can buy… on… floor”.

· Shopping centre design. This was a creative, opinion-gap task. The learner and teacher collaboratively designed a shopping centre. The student described what shops they wanted in their shopping centre. The teacher then typed these into a blank shopping centre directory with four floors. This open task was less contextualized than the birthday party invitation or the directions roleplay. The materials did not indicate why learners were designing the shopping centre (e.g. to win a design competition). No prompts were provided, implying this task was unfocused.

· Favourite food survey. This task asked learners to “list and describe” their favourite foods. The task included three pictures of food in a partially completed grid. The grid included the days of the week on the x-axis and ‘breakfast’, ‘lunch’ and ‘dinner’ on the y-axis. Learners communicated their eating habits and/or preferences. Although an answer grid was provided, this was too small for teachers to write in. This task also lacked context. The instructions did not specify why learners should describe their favourite foods.

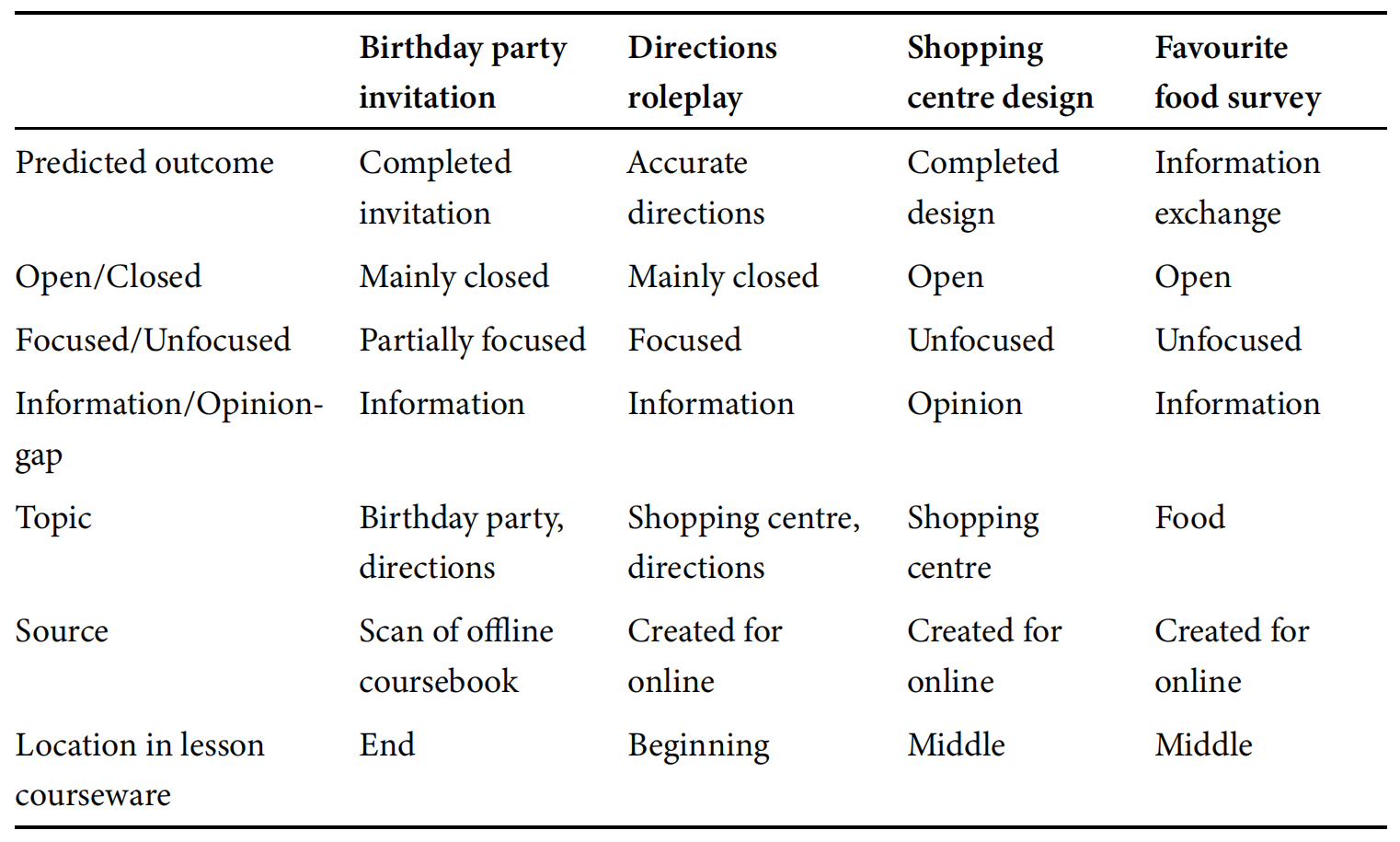

This information is summarized in Table 1.

These four tasks were chosen because:

· they were relatively close together on the same course. This allowed for the same learner-teacher dyads to be observed using different tasks.

· they varied in their openness, level of focus, detail of instructions, topic and if they included an information or opinion-gap.

· they came from different sources. Three had been designed for online classes. One had been taken from an offline coursebook.

· it was possible to find examples of these tasks in use. The tasks examined had been used frequently enough for ten examples of each to be found. This was not true of other communicative tasks in this course.

4.4 Analysis

Short segments of teacher and learner conversation using the above tasks were transcribed. These transcriptions were examined using conversation analysis. Learner utterances were the main focus of the analysis. These utterances were analysed along with those of teachers to take into account the influence of the interlocutor. Codes were generated by looking at the transcripts. Transcripts were coded, then re-coded to check for discrepancies. Three levels of codes were developed. These were:

· Did meaningful communication occur?

· What did the learners communicate?

· How did they communicate?

Meaningful communication was judged to have occurred when a learner utterance performed one of the following functions:

· Communicating role-pay information

· Communicating student’s ideas

· Communicating student’s preferences

· Communicating student’s personal information

· Negotiating meaning

· Taking control of the conversation/discourse

These were also the categories for what the learners communicated. The coding categories for how learners communicated were:

· Pushed output: when learners attempted to express something challenging. Learners did this by going beyond the confines of their interlanguage.

· Target language: when learners used language learned at a previous point in the lesson or unit to communicate.

· Existing resources: when learners used language learned previously. This included shorter utterances than were studied, single words or language that appeared to have already been acquired.

· 50/50 or yes/no: when students communicated primarily using listening. For example, when learners responded “yes” or “no” to a genuine question from the teacher.

· Non-verbal: when learners communicated by nodding, shaking their head, using a facial expression or drawing on the screen.

Not all meaningful communication is equally valuable. Some theories of SLA (such as Swain, 1985) regard meaningful communication which involves pushed output as most valuable. Others (Long, 1983) regard negotiation of meaning as most valuable. Therefore, this analysis will highlight instances of negotiation of meaning and pushed output.

Pushed output was judged to have occurred when learners went beyond the confines of the target language. Learners did this to express something meaningful to them, for example by using language creatively. Negotiation of meaning was judged to have occurred when dyads attempted to resolve a miscommunication. Such miscommunications occurred for various reasons, such as when learners misunderstood their teachers. Occasionally, poor internet connections rendered speech incomprehensible. These issues triggered requests for clarification and repetition. An example of a coded activity is given in the appendix.

After collecting and coding the data I performed a simple quantitative analysis. I counted the number of occurrences of each category of meaningful communication. These included student utterances only. The mean number of meaningful interactions per minute was calculated. This mean takes into account the varying length of the activities. A 20% trimmed mean is presented in the results and used for comparison. This was the smallest trimmed mean given the size of this data set. This was used to minimize the effect of outlying data points.

5. Results

5.1 Quantitative Results

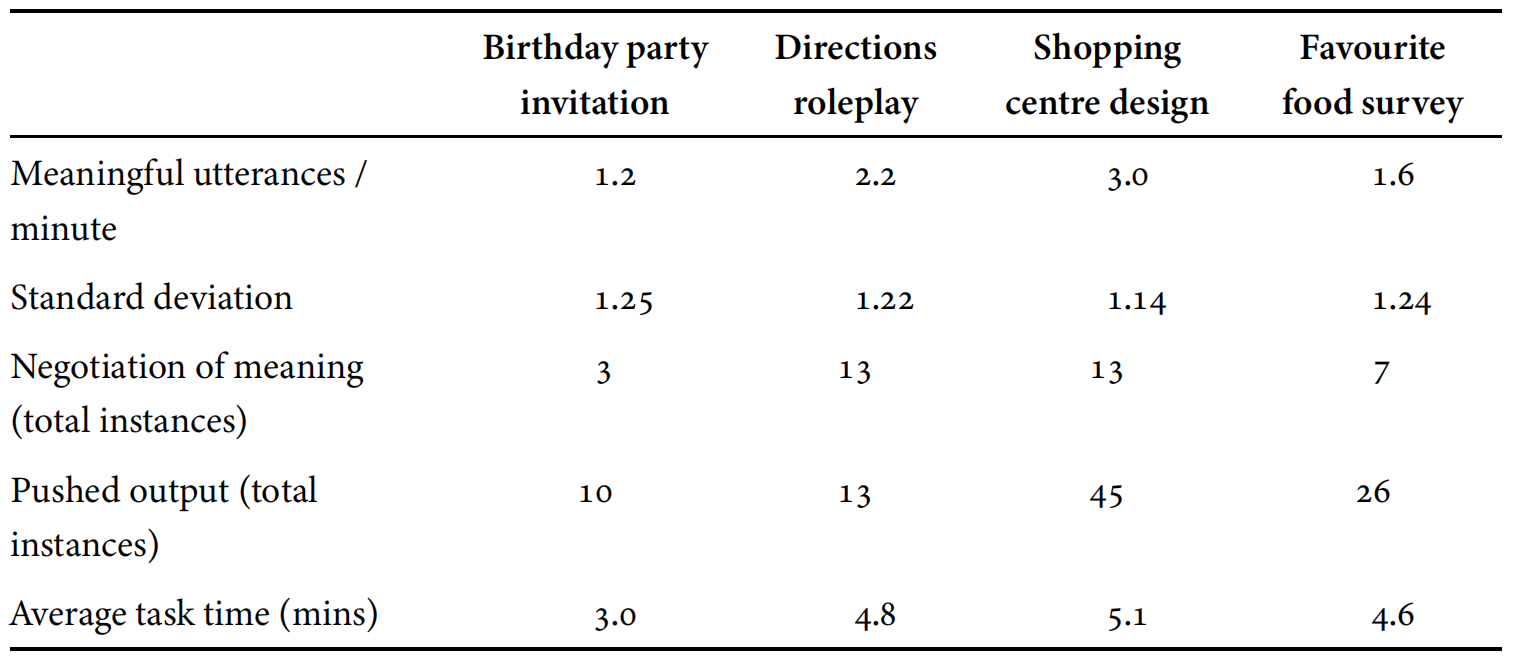

There was a considerable difference in the amount of communication that took place between the four tasks (Table 2). The shopping centre design task prompted twice as many meaningful student utterances per minute compared with the least effective task (birthday party invitation). The shopping centre design task also had the highest number of instances of both pushed output and negotiation of meaning (along with the directions roleplay). This demonstrates the effect of the task on the average amount of meaningful communication.

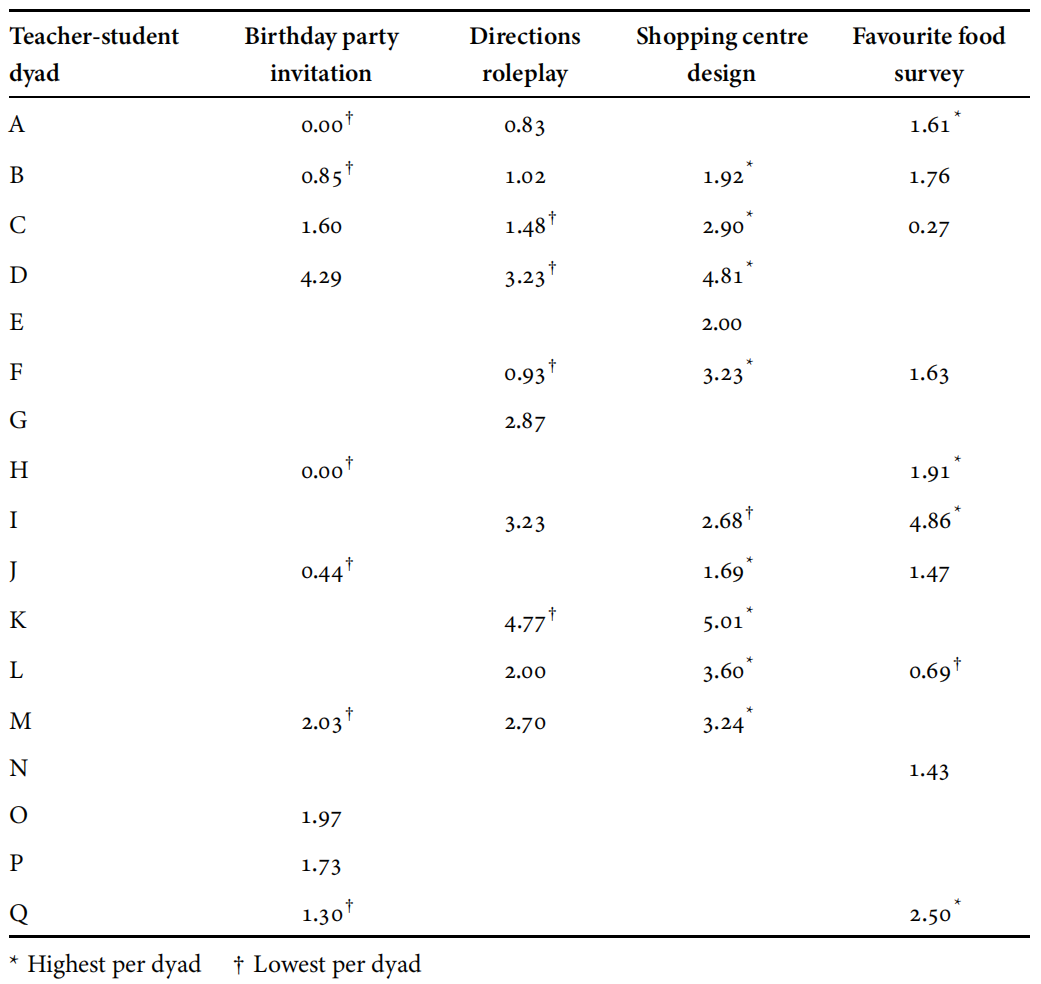

However, there was more variation among the dyads using each task than there was between the different tasks. In spite of this variation, the shopping centre design task produced the highest number of meaningful learner utterances per minute for eight of the nine teacher-learner dyads who used this task and one other task. Similarly, the birthday party invitation task resulted in the lowest number of meaningful student utterances per minute for all bar two of the teacher-student dyads who used this task and one other (table 3).

These results will now be described in more detail using excepts from teacher and student interaction.

5.2 Qualitative Results

5.2.1 Negotiation of Meaning

The shopping centre design task produced the equal highest number of instances of negotiation of meaning (13). Extract 1 gives an example of this, from a lesson that involved a high number of instances of negotiation of meaning.

Extract 1

1. Teacher: Ground floor we’re going to have a dog shop. Dog food, dog everything. Dog games, dog place to play if it’s raining. Dog shop, dog gym. Ha-ha. A dog gym.

2. Student: (draws ‘∞’)

3. Teacher: Another dog shop? No, no, no, no. We can only have one dog shop. One big dog shop.

4. Student: It’s a ca-, candy shop.

5. Teacher: Oh, a cat shop? Okay, okay, okay.

6. Student: Candy, candy shop! This is candy.

7. Teacher: Okay, alright, so we’ve got dogs, we’ve got candy…

This learner is trying to tell the teacher what shop to draw. On line 2 he tries to express meaning through a picture, attempting to take control of the discourse. The teacher misinterprets this (line 3). The student then attempts to resolve misunderstanding twice (line 4 and 6), before the teacher acknowledges (line 7). During this activity, learners appeared motivated to both communicate their own ideas and ensure their teachers understood. The task outcome (i.e. completing the shopping centre design) gave teachers a reason to listen to learners. Students were able to check their teacher’s understanding from what the teachers typed and could react to misunderstandings. Teachers could not ‘fake’ understanding and move on.

The favourite food activity on the other hand produced half as many instances (7) of negotiation of meaning. This was unexpected as the task appeared personal and included a genuine information-gap. Extract 2 shows a typical interaction:

Extract 2

1. What will you eat tomorrow? Tomorrow is Sunday. What will you eat?

2. Student: Mushroom.

3. Teacher: Mushrooms, okay. And what did you eat for lunch on Tuesday? Tell me what you ate for lunch.

4. Student: Pizza.

5. Teacher: Oh yum, pizza, I like pizza. What about Wednesday?

6. Student: Chicken.

7. Teacher: Good, you eating some good lunch. Chicken, yes. What about Thursday?

8. Student: Tomato.

9. Teacher: I ate tomato.

10. Student: I make us tomato and a rice.

11. Teacher: Oh yummy, tomato and rice, good. Okay, and dinner.

This interaction looks mechanical and follows the IRF sequence. However, some learner utterances appear meaningful (lines 4, 6 and 10). Others, such as “mushroom” (line 2) and “tomato” (line 8) are more challenging to categorize. It is possible that the learner was unsuccessfully attempting to communicate personal information. It is also likely the student was just making up foods to complete the activity. Despite the incomprehensibility of these utterances (lines 2 and 8), the teacher did not ask any follow-up questions. Instead, the teacher switched to focusing on form (line 9). In contrast with Extract 1, this teacher appears to fake understanding and move on. Why did this happen?

One possibility is the topic. Food varies greatly between cultures. Living in the USA, this teacher probably had minimal knowledge and experience of Chinese food. As a result, the teacher could not imagine what this learner was trying to communicate. Even had the teacher asked follow-up questions she may not have understood the learner. The topic was not familiar enough to the teacher to generate significant engagement and thus negotiation of meaning. This issue was exacerbated by the context: learners and teachers taking classes from different countries. This issue would be less likely to arise offline, with teachers living in the same countries as their students.

5.2.2 Pushed output

The shopping centre design task resulted in the most (45) pushed output. Extract 3 shows an example of interaction after most of the shopping centre was completed.

Extract 3

1. Teacher: What about a Minnie Mouse… Sorry?

2. Student: (draws in extra borders on the directory) One, two, three.

3. Teacher: You want more shops?

4. Student: And dancing!

5. Teacher: A dancing shop?

6. Student: No, dancing, oh… (L1)

7. Teacher: A dance school.

8. Student: No. No. A [pause] dancing school.

9. Teacher: A dance school. Dance school, okay. (Types “Dance School”) Good, very, very nice. I like the shopping centre. Do you like it?

10. Student: Yes, and… Sing. Sing school.

11. Teacher: Singing school. Okay.

This interaction begins with the teacher making a suggestion (line 1). The learner ignores this and instead takes control of the activity by adding more shops to the shopping centre directory (line 2). Later, when the teacher attempts to draw the tasks to a close (line 9), the student extends the activity again (line 10). This is evidence of high student engagement in this activity.

During the previous unit of study, this student learned vocabulary for shops. This included “gift shop”, “toy shop”, “book shop”, “supermarket”, etc. In Extract 3, the learner uses none of these lexical items. Instead, she stretches her linguistic resources to express her own ideas and preferences (lines 4, 8 and 10). Initially (line 4) she suggests “dancing”. The teacher reformulates this to “a dance shop”. The learner then appears to realize she has not conveyed her idea and hesitates. The teacher suggests a “dance school”. The learner partially accepts this, saying “a dancing school” (line 8). She ignores the teacher’s correction (line 9) then combines “school” with “sing” to create “sing school”. This was one of few observed examples of a learner combining words in novel ways. This contrasts with typical young learner teaching which often merely involves listening and repeating (Pinter, 2011). It is noteworthy that this most creative task inspired the most creative language use.

The favourite food activity produced the second highest number of instances of pushed output (26). Extract 4 shows one example.

Extract 4

1. Teacher: And lunch?

2. Student: In lunch, I, I, I eat this too. I eat school lunch. I eat school lunch.

3. Teacher: Are the lunches in school good?

4. Student: I don’t know what is school lunch.

5. Teacher: It’s a surprise every day?

6. Student: Yes.

7. Teacher: Are school lunches good, are they okay or are they ew!?

8. Student: Sometimes it’s okay. Sometimes it’s ew.

The student initially attempts to convey a simple idea (line 2), that he eats lunch at school. On line 4 the student expresses a more complex idea, using pushed output to communicate that school lunches are different every day. The teacher paraphrases (line 5), providing the learner with salient and meaningful input. While the task here is the same as that in Extract 2, the resulting communication is quite different. In Extract 2, the topic was Chinese food, which was unfamiliar to the teacher. In Extract 4, the topic was school lunches, which was familiar to both teacher and learner alike, allowing for mutual understanding.

5.2.3 Timing

The birthday party invitation was on the final page of a lesson. Teachers spent 38% less time on this task than on the other tasks (table 2). Excerpt 5 shows an interaction in the final seconds of a lesson.

Excerpt 5

1. Teacher: Where is, you’re going to put, where is your home?

2. Student: (Reads the instructions.) Please come to my birthday party on. Birthday party.

3. Teacher: Put today’s date, the tenth of the tenth, two thousand and nineteen at ten AM (writes “10/10/19” “1000 am”). Where’s your house, are you going to go here or here?

4. Student: Left, left.

5. Teacher: So that can be your house and that can be my house. How am I going to get to your house?

6. Student: Take the MTR to…

7. Teacher: Say exit one.

8. Student: Exit one.

9. Teacher: Turn…

10. Student: Turn left. My house is opposite the restaurant.

On line 3 the teacher removes the choice of date (i.e. chooses the student’s birthday for him!) as well as the time of the party. This leaves the student with only one choice: which house is his (line 4). On line 5 the teacher assumes the role of the invitee to the party (“How am I going to get to your house?”). This denied the learner the choice of who to invite to his party. The teacher tells the student what to say again on her next turn (line 7). Why did this teacher take control of this task from the student? This task was located on the last page of a lesson. Many dyads completed this task in the final minutes of class. Under these time constraints, teachers prioritized task outcome (completed invitation) or accuracy over meaningful communication. It also possible that the teacher in Except 5 was unaware of the purpose of this task.

5.2.4 Drill-like Interactions

The directions roleplay produced the equal highest number of instances of negotiation of meaning (13). However, over half of those were produced by one dyad. Although this task produced the second highest number of meaningful student utterances per minute (2.0 per minute), many of these interactions sounded drill-like, such as Excerpt 6.

Excerpt 6

1. Teacher: So, is there a coat? Is there a coat?

2. Student: Yes, there is.

3. Teacher: You can buy one on…

4. Student: You can buy coat on… You can buy coat on first floor.

5. Teacher: On the first floor, fantastic, good. On the first floor, great. Alright. Is there a present?

6. Student: You can… You can. You can buy, buy present on. You can buy present on a fourth floor.

7. Teacher: On the fourth floor, lovely. Is there a storybook?

8. Student: You can buy storybook on fifth floor.

9. Teacher: On the fifth floor, fantastic. Is there trainers?

10. Student: Trainers. You can buy trainers on, on second floor.

This interaction followed the IRF sequence, closely following the sentence stems on the courseware. The influence of the sentence stems was so great that the teacher produces a grammatically incorrect utterance (line 9). Ghosn (2003, p. 294) describes observing a similar activity where students read phrases from their coursebook. This “became more of a drill or a decoding exercise than genuine communication”. Long notes, “Scripted talk, [when] read aloud, typically lacks such features of natural conversation” (Long, 2015, p. 250). Here the sentence stems focused the task to the extent that it took on the quality of a substitution drill.

5.3 Summary of Results

Returning to the research questions:

1 How effective are four tasks in supporting meaningful spoken language production of beginner level Chinese young learners in online language lessons? This varied considerably between the tasks. The most successful task produced twice the number of instances of meaningful communication as the least effective task. It also resulted in the highest number of meaningful learner utterances per minute for eight of the nine teacher-learner dyads who used this task and one other. The least successful task was similarly consistent in its ineffectiveness.

2 Which types of tasks are most effective in encouraging learners to demonstrate the elements of meaningful communication? The most effective task was an open task that included a tangible outcome. The task required teachers to listen and react to the meaning of the learners’ utterances. Furthermore, this task appeared to motivate learners, some of whom extended the length of the activity. This in turn appeared to inspire learners to negotiate meaning with their teachers and take control of the classroom discourse. This contradicts findings that indicate closed tasks are more likely to result in negotiation of meaning than open tasks (Ellis, 2013).

I will now put forward recommendations for online task design which supports spoken language production of beginner level young learners based on these results.

6. Implications

The following recommendations are given for increasing meaningful communication between young learners and teachers in online one-to-one tasks.

1 Design open opinion-gaps which motivate young learners to be creative. Learners appeared most motivated to communicate their ideas and opinions. They were less motivated to communicate personal information. In the most successful task, learners frequently took control of the discourse. Interactions deviated significantly from the IRF sequence, in spite of this task’s lack of contextualization. This supports the notion that engagement in tasks is a strong determiner of learner participation. It also indicates that young learners may be less concerned with the context of a task. For the tasks examined here, the more creative and open the task the more frequently learners produced pushed output.

2 Include tangible task outcomes which allow learners to check they have been understood. The most successful task involved learners collaborating with the teacher to create a plan for a shopping mall. This task outcome appeared to have two advantages. Firstly, the outcome focused learners and teachers on meaning as opposed to form. Secondly, it allowed learners to check they had been understood by the teacher. This outcome prevented teachers from faking understanding and moving on. When learners realized they had been misunderstood, they negotiated meaning.

3 Place communicative tasks near the beginning of a lesson sequence. Teachers spent least time on the task at the end of a lesson sequence (the birthday party invitation). This task was often squeezed into the final two or three minutes of lesson time. Under this time pressure, teachers prioritized accuracy or outcome over communication. Some teachers took over the learners' role to complete the activity as quickly as possible. This is of particular importance to teachers teaching online. Completing activities out of order is more challenging online than offline.

4 Avoid providing sentence stems on the same page as a task. The task which included sentence stems (directions roleplay) tended to produce interactions in which teachers prioritized form over meaning, closely following the prompts. Student output in this activity was reminiscent of a substitution drill. In face-to-face classrooms, teachers can hide prompts by asking students to close their coursebooks. If a teacher writes sentence stems on the board, they may erase these as an activity unfolds. In this online context, the materials could not be minimized or hidden. Thus, these sentence stems appeared to have a bigger influence than they would have offline. If necessary, prompts and sentence stems could be included on a previous courseware page.

5 Ensure task topics are familiar to students and teachers. Topic familiarity has been identified as an important factor for learner success on tasks (Long, 2015). In online one-to-one classes, teachers must also be familiar with topics if tasks are to be successful. The favourite food task involved learners describing their favourite foods. This task led to relatively little meaningful communication. This may have been due to a lack of shared understanding about local foods. Although these learners and teachers took classes together in the same online space, they were living on different continents. As a result, the teachers knew little about the foods the learners described to them. Unable to understand what learners described, teachers faked understanding and moved on. These ‘topic culture gaps’ are thus unique to online classes and need special attention from writers.

6 Indicate the purpose of tasks in online materials. Ellis notes that “a task may have been designed to encourage a focus on meaning, but when performed by a particular group of learners, it may result in display rather than communicative language use” (Ellis, 2013, p. 5). In these one-to-one classes, the was true of certain teachers. Some teachers used communicative tasks to focus on accuracy or task completion instead of meaning. While the purposes of different stages of lessons are clear to materials writers, they will be less clear to teachers. This is even more likely to be the case for online teachers given their lack of experience and training.

7. Conclusions

This research set out to evaluate the impact of tasks on the level of meaningful communication between teachers and learners. The teachers and learners observed used these tasks in ‘real-classroom conditions’ in their regular classes. There are limitations to this study and its recommendations. The analysis focused only on a small number (seventeen) of dyads. This means that the results offer more in the way of insights than generalizations. Other limitations include the choice of tasks. These varied in their degrees of contextualization and clarity of instructions. The omission of the ages of the learners is also significant. Age differences in young learners have been found to affect performance on tasks (Oliver & Azkarai, 2017). Furthermore, including the voices of the teachers could have furthered understanding of these interactions.

In spite of these limitations, this research indicates that tasks have a large effect on meaningful communication. The most successful task (shopping centre design) produced twice the number of instances of meaningful communication as the least effective task. It also resulted in the highest number of meaningful learner utterances per minute for eight of the nine teacher-learner dyads who used this task and one other. The least successful task (birthday party invitation) was similarly consistent in its ineffectiveness. This least effective task was the only task not designed for online one-to-one lessons. This supports Hampel’s premise that an “easy (and cheap) transposition of face-to-face tasks to a virtual environment is not possible” (Hampel, 2006, p. 111). Instead, materials writers must design tasks specifically for this context. Effective online tasks must account for the affordances of the virtual environment as well as the motivations of young learners.

8. Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Russell Stannard for his unending encouragement, ideas and feedback over the course of this research project.

References

Arnold, W., & Rixon, S. (2008). Materials for Teaching English to Young Learners. In B. Tomlinson (Ed.), English Language Learning Materials (pp. 38-58). Continuum.

Blake, R. J. (2017). Technologies for Teaching and Learning L2 Speaking. In The Handbook of Technology and Second Language Teaching and Learning (pp. 107-117). John Wiley & Sons

Cunningsworth, A. (1998). Evaluating and Selecting EFL Materials (1st ed.). Heinemann.

DeKeyser, R. (2007). Practice in a Second Language: Perspectives From Applied Linguistics and Cognitive Psychology (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Ellis, R. (1999). Understanding Second Language Acquisition. Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.

Ellis, R. (2009). Task-based language teaching: Sorting out the misunderstandings. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 19(3), 221-246.

Ellis, R. (2013). Task-based Leanguage Learning and Teaching (2nd ed.). Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.

Ellis, R. (2019). Introducing Task-based Language Teaching (1st ed.). Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.

Ellis, R., & Shintani, N. (2014). Exploring Language Pedagogy through Second Language Acquisition Research (1st ed.). Routledge.

Ellis, R., Skehan, P., Li, S., Shintani, N., & Lambert, C. (2019). Task-based language teaching: Theory and practice. Cambridge University Press.

Ghosn, I.-K. (2003). Talking like texts and talking about texts: How some primary school coursebook tasks are realized in the classroom. In B. Tomlinson (Ed.), Developing Materials for Language Teaching (pp. 291-305). Continuum.

Hampel, R. (2006). Rethinking task design for the digital age: A framework for language teaching and learning in a synchronous online environment. ReCALL, 18(1), 105–121.

Hampel, R. (2009). Training teachers for the multimedia age: Developing teacher expertise to enhance online learner interaction and collaboration. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 3(1), 35-50.

Johnson, K. E. (1995). Understanding Communication in Second Language Classrooms (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Long, M. (1983). Process and Product in ESL Program Evaluation. TESOL Quarterly, 17, 409-25.

Long, M. (2015). Second Language Acquisition and Task-Based Teaching (1st ed.). John Wiley and Sons, Inc..

Nunan, D. (1987). Communicative language teaching: Making it work. English Language Teaching Journal, 41, 136-45.

Oliver, R. (1998). Negotiation of meaning in child interactions. The Modern Language Journal, 82(3), 372-386.

Oliver, R., & Azkarai, A. (2017). Review of Child Second Language Acquisition (SLA): Examining Theories and Research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 37, 62-76.

Pinter, A. (2011). Children learning second languages. Research and practice in applied linguistics (1st ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Shintani, N. (2014). Using tasks with young beginner learners: The role of the teacher. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 8(3), 279-294.

Swain, M. (1995). Three functions of output in second language learning. In Principle and practice in applied linguistics: Studies in honour of H. G. Widdowson (pp. 125-144). Oxford University Press.

Tomlinson, B. (2020). Assisting Learners in Orchestrating their Inner Voice for L2 Learning. Language Teaching Research Quarterly, 19, 32-47.

Tomlinson, B., & Masuhara, H. (2018). The complete guide to the theory and practice of materials development for language learning (1st ed.). Wiley and Blackwell.

Ziegler, N. (2016). Synchronous Computermediated Communication and Interaction: A Meta Analysis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 38, 553 – 586.